This post was co-written by Horangi Cyber Operations Consultant Sangsoo Jeong.

Introduction

Horangi recently experienced an internal security incident through a phishing email that attempted to deliver a malicious payload. The combination of security awareness, vigilance of Horangi employees, an established incident response, and the preparedness of the internal security team allowed the incident to be prevented.

In this blog post, we share the best practices of incident preparedness and incident response supported by examples and lessons drawn from the above mentioned incident. This includes new approaches for java-based malware analysis, as well as the interesting findings garnered from the Pyrogenic/Qealler malware analysis. We applied a new technique of analyzing Java heap dumps to extract the IPs of Command and Control (C2) servers. In doing so, we found a backup C2 IP which could not otherwise have been detected from network traffic.

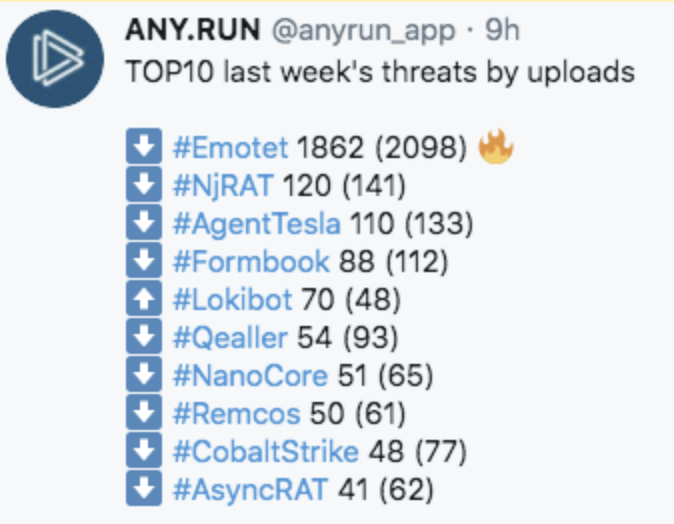

The malware that we encountered was found to be classified as a Trojan information stealer. It disguises itself as a benign file (in this specific scenario, a remittance request), but when it is executed, it runs hidden functions and steals information such as mailbox login credentials from Outlook, and passwords from browser databases (including Chrome and Firefox). In successful attempts, the information would be sent to a remote server, C2, which is controlled by a malicious actor. ANY.RUN, an interactive online malware sandbox, identified the family of such malware to be in the top 10 malware threats of late.

Incident

Attack Vector

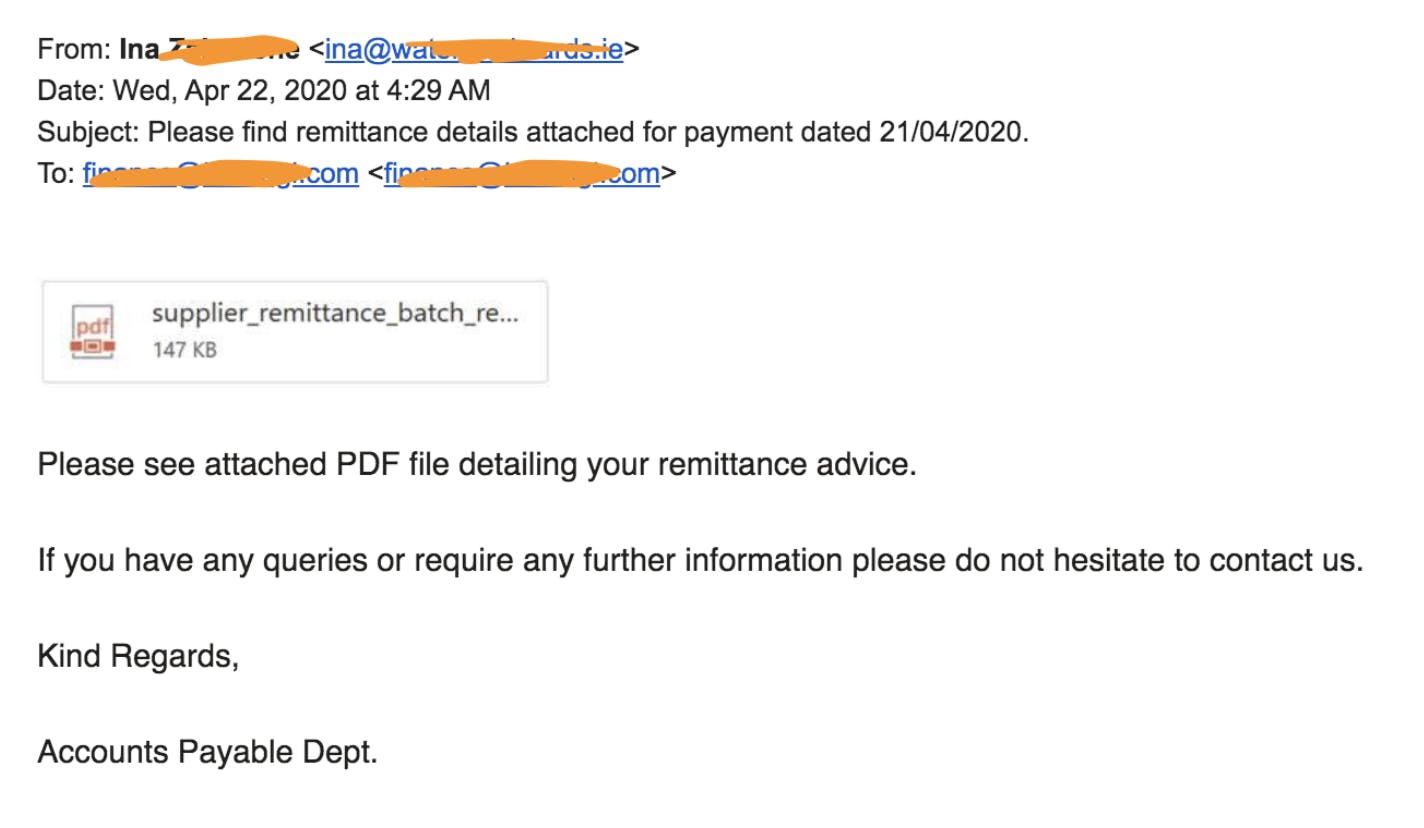

A member of the Horangi Finance team received a phishing email which was designed to look like remittance advice containing a PDF attachment.

The PDF attachment that you see was actually an image with a link. In spite of Horangi enabling advanced phishing protection in Google Suite, Gmail did not identify and categorize this email as a phishing threat and failed to provide a security warning to the user. When the employee clicked on the image, it opened the link in a new tab on the browser and downloaded a malicious JAR file. The victim believed that it was an archived file but after unpacking it, they noticed that the content seemed strange and immediately informed the Internal Security team.

Triage

Continuous monitoring of the activity in this mailbox allowed the Internal Security team to respond immediately to this incident. The team reached out to the employee and informed them that it was, indeed, a phishing email. After running through and confirming the series of actions taken by the employee, the team advised that they do not touch the downloaded file and ran an antivirus scan which they monitored for any suspicious activity (e.g. unusual pop-up windows).

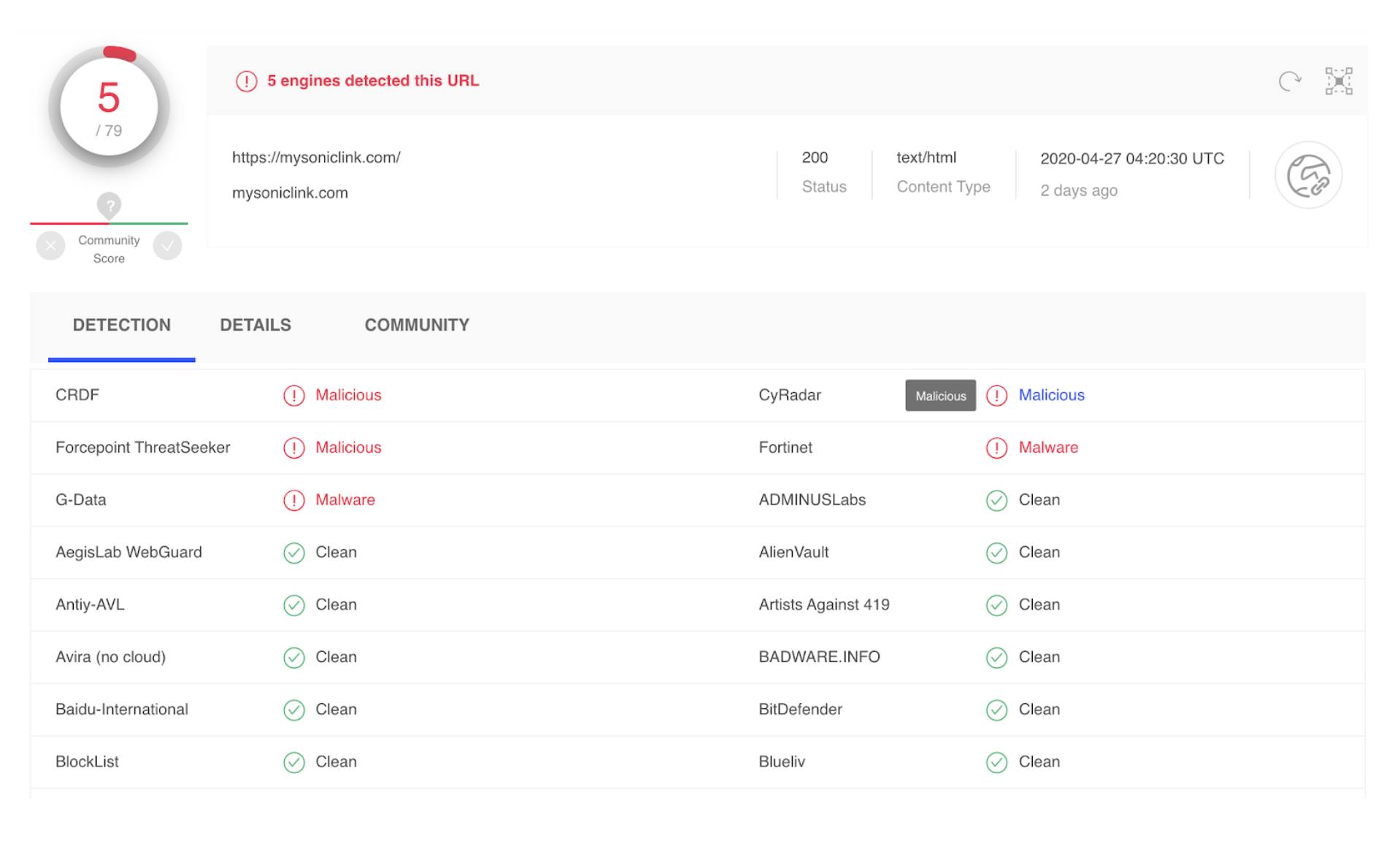

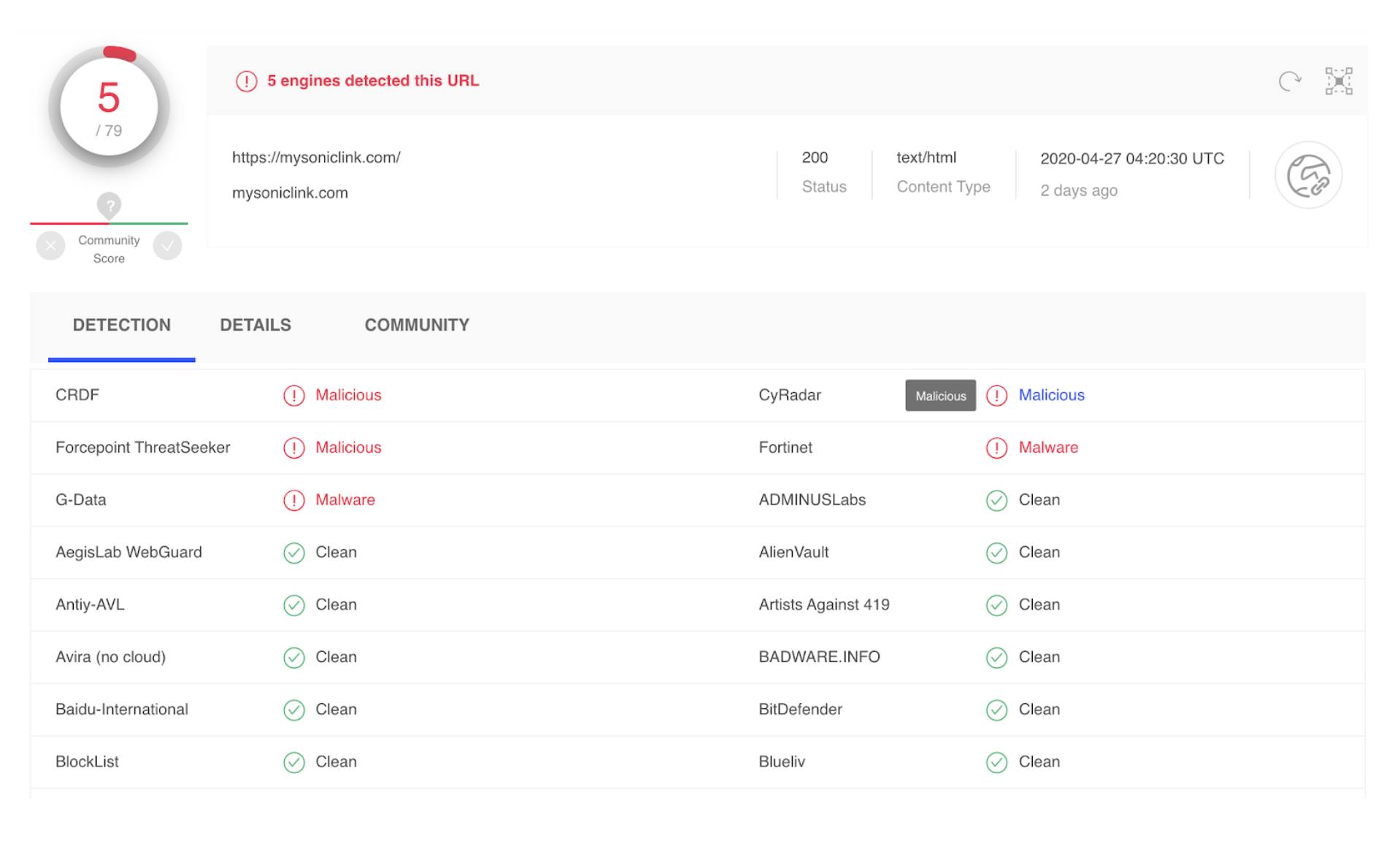

Following which, the Internal Security team triaged the incident by first accessing the link from the phishing email in their local sandbox and downloading the malicious file. The security team then searched the URL and the hash <d469fbd9d4299ab767db9054cf2a87b60d8e0f76bd002b588f0f335b1b6c25ec> of the downloaded file on VirusTotal. A file with the same hash had been uploaded to VirusTotal by another victim just hours before and it was classified as a generic Trojan by only a few antivirus engines. At the time, the URL was not identified to be suspicious but was classified as malicious by a few engines by the next day.

Analysis

As none of the antivirus engines in VirusTotal flagged the file to be part of a specific malware family, the Internal Security team could not know the malware’s behaviour. As such, the team decided to analyze the malware to extract Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) and monitor the victim’s system. There was also a possibility that the victim had already unknowingly executed the malicious file so the team also needed to monitor the threat.

In summary, our flow of the analysis consisted of the following steps:

- Decompile Java malware

- Find a suitable starting point

- Begin debugging

- Arrive at an important state of the malware

- Take a heap dump

- Analyze the heap dump

1. Decompile Java malware

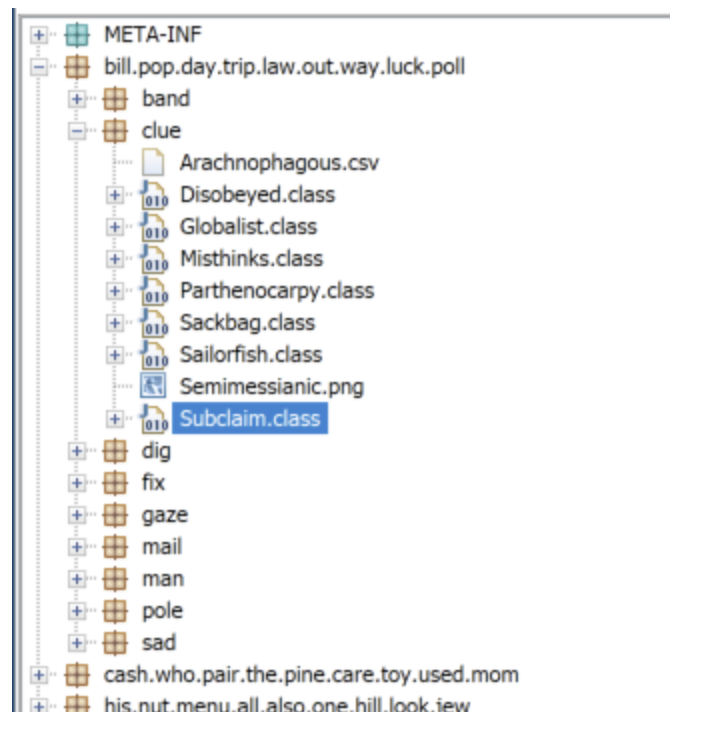

The analysis started with the decompilation of the malware to understand its high-level structure. The JAR file was easy to reverse with tools such as JD-GUI. However, the team faced a highly obfuscated structure of files in the reversed package. The figure below shows the random names of packages and classes.

2. Find a suitable starting point

The team knew that they would need to dynamically analyze it. Still, it would be difficult to try all the possible different scenarios of the execution. Thus, they first kept searching in the code for an interesting starting point from which they could start the debugging.

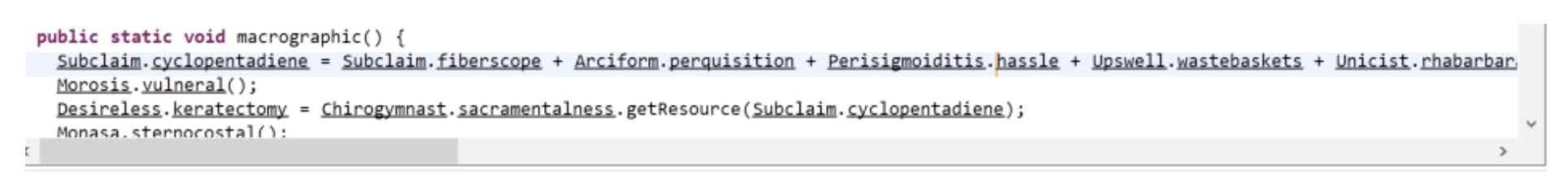

Then, they looked for possible functions of the malware in the source code, such as communication to the Internet or operations with the file system. The team found that it was constructing a path to a file that we believed it wanted to load.

3. Begin debugging

The team used a combination of static and dynamic analysis. After they found an interesting part of the code that contained a path to a file that was prepared to get loaded, they wanted to know exactly what happened with that file. It was tricky to track where the file was loaded in the source code so we began debugging and discovered that the malware loads q0b4.bootstrap.templates.Header. The team did some research on it and stumbled upon a blog post on Securityinbits about a similar malware. Following the guide in the blog post, we managed to extract the additional Java classes and found the names of the variables.

4. Arrive at an important state of the malware

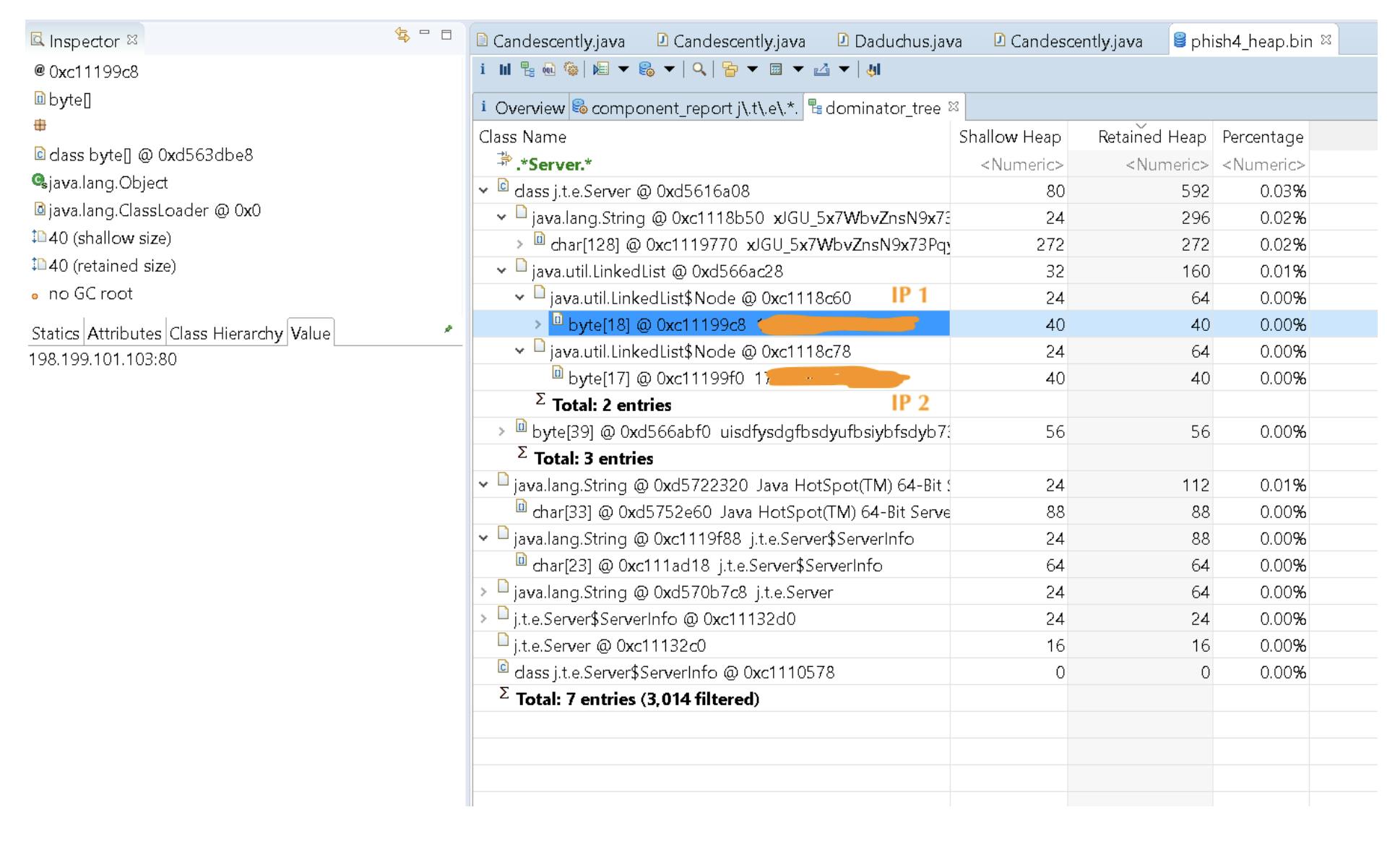

The malware needed to execute its main malicious function — stealing and exfiltrating data. So the team looked for a state in which the malware prepared to connect to the C2 servers. They identified that they needed to look for values of serverIPs variables of a Server class which should store IP addresses of C2 servers.

The security team then also decided to dump and analyze the process’s memory when it loaded the Header class and contacted IP addresses stored in serverIPs list variable.

5. Take a heap dump

The team set up a breakpoint right before the malware loaded the Header class and took a heap dump right after releasing the breakpoint. Then they took the heap dump with the JDK tool jmap

jmap -dump:format=b,file=C:\Users\Nico\phish_heap.bin 3796

Where 3796 is the process id of javaw.exe, the executed malware, observed through Process Explorer.

6. Analyze the heap dump

Following that, the team opened and analyzed it with the Eclipse’s Memory Analyzer plugin.

They opened the heap dump phish_heap.bin as a Component Report and searched for the j\.t\.e\.* package. Then, they opened the Overview tab and clicked on Dominator Tree on which they searched the Server keyword.

They found two IP addresses.

The first IP address had been detected and identified by several search engines on VirusTotal as suspicious. However, the second IP address was clean. The team has strong reason to believe that it was a dormant C2 server that the malicious actor would use in the event the first IP address is blocked.

Remediation and Sharing with the Community

The abovementioned IP addresses have been shared with the community of trusted cybersecurity researchers. The team then notified the second IP address’s hosting provider, Linode, that this IP address was found in the malicious sample.

Recommendations

Phishing awareness among employees, the prepared and practiced incident response from the Internal Security team enabled Horangi to detect and contain the incident swiftly.

After an analysis of the incident, the Internal Security team shared the lessons drawn with anonymized data to further educate and improve the security awareness among employees, as well to build up the skills of the Internal Security team.

Incidents are inevitable even within security companies. We recommend that every company:

- Train employees company-wide for phishing awareness and security awareness in general

- Have a clear point of contact in the company to which employees can report security incidents

- Prepare and practice an incident response program

- Have a clear escalation path when building an incident response capability internally and engaging an external service provider

- Do not rely solely on technical solutions (antivirus, security settings of GSuite etc.)

- Keep abreast of threats within their region and industry